If I had to pick a favorite American writer, it would be Mark Twain, and if I had to pick a favorite scene from an American novel, it would be the one where his unlikely hero, Huckleberry Finn, accepts his fate in hell.

It’s the moral climax of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The duke and dauphin have betrayed Jim and sold him to the Phelpses “for forty dirty dollars,” and the Phelpses have locked Jim in their shed, where he awaits his return to his rightful owner for a $200 reward. Huck goes back to the raft to figure out what to do next, and there he gets to thinking about the lessons he learned in Sunday school about what happens to people like him who assist runaway slaves.

“People that acts as I’d been acting about [Jim],” he’d been told, “goes to everlasting fire.”

(After all, the Bible is clear: “Slaves obey your earthly masters with respect and fear”- Ephesians 6:5.)

Huck feels genuine conviction regarding his sin and, fearful of his certain fate in hell unless he changes course, he decides to write a letter to Jim’s owner, Miss Watson, to tell her where Jim can be found:

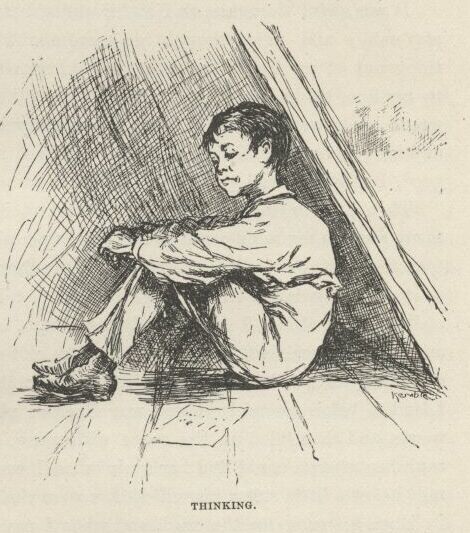

I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time I had ever felt so in my life, and I knowed I could pray now. But I didn't do it straight off, but laid the paper down and set there thinking- thinking how good it was all this happened so, and how near I come to being lost and going to hell. And went on thinking. And got to thinking over our trip down the river; and I see Jim before me, all the time; in the day, and in the night-time, sometimes moonlight, sometimes storms, and we a floating along, talking, and singing, and laughing. But somehow I couldn't seem to strike no places to harden me against him, but only the other kind. I'd see him standing my watch on top of his'n, stead of calling me, so I could go on sleeping; and see him how glad he was when I come back out of the fog; and when I come to him agin in the swamp, up there where the feud was; and such-like times; and would always call me honey, and pet me, and do everything he could think of for me, and how good he always was; and at last I struck the time I saved him by telling the men we had smallpox aboard, and he was so grateful, and said I was the best friend old Jim ever had in the world, and the only one he's got now; and then I happened to look around, and see that paper.

It was a close place. I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a trembling, because I'd got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:"All right, then, I'll go to hell"- and tore it up.

It was awful thoughts, and awful words, but they was said. And I let them stay said; and never thought no more about reforming. I shoved the whole thing out of my head; and said I would take up wickedness again, which was in my line, being brung up to it, and the other warn't. And for a starter, I would go to work and steal Jim out of slavery again; and if I could think up anything worse, I would do that, too; because as long as I was in, and in for good, I might as well go the whole hog.”

It is a moment of true moral courage, complicated though it is by troubling ingrained cultural assumptions. (Later, Huck can only make sense of Jim’s kindness to him and Tom Sawyer by concluding he must be “white on the inside,” a comment that reveals Twain’s gift for creating characters that both critique yet fully inhabit their cultural contexts.)

I often think about Huck’s resolution when I am told by religious leaders that “the Bible is clear” on this or that, and that I’ve got to stop listening to those gut feelings that tell me maybe we’ve gotten a few things wrong, that maybe there’s more to the story than we’re ready to see.

“Your feelings don’t matter,” they say.

“Your feelings cannot be trusted,” they say.

“Once you start listening to your feelings, over and beyond the plain meaning of Scripture, it’s a slippery slope to hell,” they say.

A part of me agrees. I want to be faithful to the inspired words of the Bible, not bend them to fit my own desires and whims. Being a person of faith means trusting God’s revelation, even when the path it reveals is not comfortable.

But another part of me worries that a religious culture that asks its followers to silence their conscience is just the kind of religious culture that produces $200 rewards for runaway slaves. The Bible has been “clear” before, after all—in support of a flat and stationary earth, in support of wiping out entire people groups, in support of manifest destiny, in support of Indian removal, in support of anti-Semitism, in support of slavery, in support of “separate but equal,” in support of constitutional amendments banning interracial marriage.

In hindsight, it all seems so foolish, such an obvious abuse of Scripture.

...But at the time?

Sometimes true faithfulness requires something of a betrayal.

A few months ago, I was invited to serve communion at a church in San Diego that included quite a few LGBT Christians in its membership. A lot of things happened in that service that would make some of the leaders in my evangelical religious community very angry: a woman serving the bread and the wine, a lesbian couple partaking of the elements with their baby daughter in tow, a gay man embracing me in a big bear hug and telling me that it was the first time in twenty years he felt worthy to come to the Table.

In that moment—the one with the big bear hug—I knew what my Sunday school teachers would say. They would say that this man was most certainly not worthy to come to the Table, that I was most certainly not worthy to serve, and that daring to participate in this endeavor would surely take me one step closer to “everlasting fire.”

“The body of Christ, broken for you,” I said anyway.

“The blood of Christ, shed for you,” I said anyway.

“The body of Christ, broken for you,” he said anyway.

“The blood of Christ, shed for you, he said anyway.

As we embraced, I knew in a way that I cannot put into words that sharing communion with this man was the right thing to do, that it was an act of bravery and grace for both of us—together unworthy, together worthy, brother and sister, in the mystery of the Eucharist.

So when the thought of my Sunday school teachers’ disapproval crossed my mind, the only words to surface to my lips were, “All right, then, I’ll go to hell.”

Perhaps grace, like the Bible, was never meant to be "sivilized" anyway.

***

© 2012 All rights reserved.

Copying and republishing this article on other Web sites without written permission is prohibited.