So far, our interview series has included an atheist, a Catholic, an Orthodox Jew, a humanitarian, a Mormon, a Mennonite, a theistic evolutionist, a Calvinist, and a gay Christian. On Thursday I’ll introduce Frederica Mathewes-Green as our Orthodox Christian!

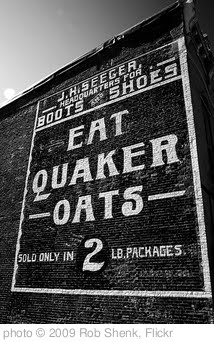

But today we’re talking with a Quaker.

Robert Fischer is a master’s student at Duke Divinity School and a member at Durham Friends Meeting. He’s on the board of Quaker House of Fayetteville, a group that works with conscientious objectors in the military, and works with Urban Ministries of Durhamand The Metta Center.

You posed some challenging questions to Robert, and I’m so pleased with the gracious and thoughtful way he responded to them. If you want to learn more, check out Robert’s blog or follow him on Twitter.

From Rachel: Can you explain the differences between conservative Quakerism, liberal Quakerism, and pastoral Quakerism?

On the whole, Quakers don’t worry about boundaries and labels much. Although you find the occasional schismatic or denominationalist flare-up in Quaker history, the general culture of Quakerism (especially these days) avoids policing the boundaries of the church. Quakers don’t worry about doctrines, but instead welcome anyone who wishes to engage in the practices of worship and community with us. It is really astounding to see this in practice, and it is something I have found only in Quakerism — and that is coming from someone who was historically a part of a hyper-welcoming liberal protestant congregation!

But you’ll often hear Friends apply the terms “liberal Quaker,” “conservative Quaker,” and “pastoral/evangelical Quaker” to themselves or others, so let me take a shot at explaining those terms. As I do so, please remember that the terms are rather vague and often relative. My own meeting, Durham Friends Meeting, is called conservative by many other Quaker congregations and is formally affiliated withNorth Carolina Yearly Meeting (Conservative), but would certainly be considered liberal by others. This affiliation is not exclusive, however — our meeting actually has a double affiliation: in addition to the conservative yearly meeting, we also associate with the liberal Quakers through Piedmont Friends Fellowship.

I identify as a conservative Quaker. What I mean when I say this is that I am “Christo-centric” — that is, my religious understanding centers on Jesus the Christ. I also mean that I appreciate Quaker “silent worship” (although I prefer to call it “waiting worship”), as well as the Quaker ecclesiological emphasis on equality and reconciliation. I very much appreciate the term “Society of Friends”, because that reminds me of my relationship to Christ Jesus—I am his friend as long as I do as he commands (John 15:14-17). Most generally, the term “conservative” means that I find myself more often than not appreciating the earliest Quakers’ insights into the nature of faith, church, and society. The term “conservative” can be read to mean “conserving historical Quaker witness”. People more conservative than I (such as Quaker Jane) sometimes even conserve historical Quaker dress, speech, and the like.

In one direction from “conservative”, you have evangelical Quakers. Worldwide, these are the most populous of the Quaker meetings, and they’re also quite populous west of the Mississippi River here in the USA. They are more traditionally Christian than conservative Quakers, and have abandoned certain Quakers witnesses in adopting a form of religious practice more familiar to Protestants. They may have formal liturgies, may have pastors (sometimes called “released ministers”), and may even recognize and practice communion and water baptism. Some even have de facto creeds.

In the other direction from “conservative”, you have liberal Quakers. Liberal Quakers—in the most stereotyped sense—have largely left Christ and the Bible behind as cultural vestiges accidental to the true message of Quakerism. They usually retain the silent worship, although I’m not entirely sure how they account for the experience there. Liberal Quakers have an affinity for the language of Quakerism (especially “Light” and “Inner Light”), but seem to be a bit cagey about what that means. The best apology for liberal Quakers that I know of is found in Quakers: A Very Short Introduction, and I will refer you there for more information. The most entertaining description of liberal Quakerism that I know of is the video for Jon Watts’ “Friend Speaks My Mind”.

So what actually unites Quakers if they are so diverse?

Within the church, the Quakers are united through orthopraxy: We have a similar set of practices, even as certain churches push those boundaries with liturgies (programmed worship) and pastoral leadership of worship. The waiting worship which Quakers are (in)famous for is one of the practices that unite us. Another our way of doing business, which is conducted worshipfully and without voting. Since there is no voting in meetings, we are obliged to practice reconciliation and mutual understanding even within our own meetings for business.

In the outside world, the unity of Quakers is cultural: a shared set of practices and a shared approach to life. In this way, Quakerism really is like a spiritual family: there is a diversity of people, but something deep inside unites them. Here are some highlights of how that “something deep inside” is expressed (commonly called “testimonies” or “witnesses”):

Peace. This can take various forms (including “Fighting Quakers” like Major General Smedley Butler), but the basic idea that the core of the gospel and the core of the Quaker mission is ultimately peace, both spiritual and worldly.

Simplicity. Sometimes called Plainness, this is basically humility in action, and an effort to place God at the center of living. Don’t consume more than you can. Stay focused on your callings. Let your yay be yay and your nay be nay.

Community. We do not leave anyone in the community without a voice—hence, the consensus way of Quaker decision-making. Community requires learning to recognize that of God in the other even when they do not seem to be making it apparent, and it requires developing real-world relationships.

Seeking. This is not normally listed as a testimony of the Friends, but I absolutely think it is central to Quaker identity. This is the idea that we are all being led, and we all must seek our leadings. We may be seeking deeper truths, we may be seeking more integrity in our expression of ourselves, or we may simply be seeking clarity in your leading, but all Quakers are eternally seeking.

From Elizabeth: What exactly is the "Inner Light"? Is this another word for the Holy Spirit or is it separate? Do all people have Inner Light, or only believers?

If there is one belief that can be said to unite Quakers, it is the belief in the universal Inner Light. All people have it, and it is this Inner Light which guides our development and our conscience and teaches us all to recognize truth.

There are a lot of stories about the earliest Quakers going to the ends of the Earth, to a variety of peoples called “heathen”, and checking to see if they, too, had the Inner Light. Lo! and behold!, these earliest Quakers recognized the Inner Light in all the people they so examined. That’s good, because that’s exactly what we’d expect from scripture (John 1:4). Through time, the ubiquitous Inner Light has become the core concept in all of Quakerism.

Personally, I recognize the Inner Light as being the Holy Spirit, the medium of Jesus’ conception and the source of our own personal connection to God. I have yet to encounter someone without the Inner Light, although I have met plenty who have trouble recognizing it or giving it the credit that it is due.

The role of the Inner Light is to be the teacher promised to us (Jeremiah 31:31-34) and the immediate Advocate of God within our souls. The Inner Light reveals the truth to us, and also convicts us of our sins, driving us towards ever-increasing sinless perfection in the image of the Lord. This is not always a pleasant experience, but it is truly the most beneficial relationship one can have. This is the key concept of personal salvation to me, and I am firmly within the Quaker tradition in having this view.

So the question may arise: “Why not just call it the Holy Spirit?” I’d give two answers. First, it is not a matter of doctrine that the Holy Spirit is the Inner Light. That is my interpretation based off of my Trinitarianism. There are plenty of other interpretations among Friends, including those that make no reference to God at all. Second, the description of “Inner Light” reflects many peoples’ immediate experience of the Holy Spirit, including both George Fox and Augustine. So calling it the “Inner Light” speaks to the experience of God, not to doctrines about God, and therefore keeps a proper emphasis.

If you are a theologian of the Catholic, Lutheran, or Holiness tradition, you can wrap your head around the practicalities of the “Inner Light” by thinking of it as “prevenient grace”. We partake of grace by means of the Holy Spirit/Inner Light. The fact that nobody can be brought to faith through their own works but must come to God through grace implies that even before we come into faith, we have grace. Therefore, even before we come into faith, we are partaking of the Holy Spirit. If you’re a theologian but prevenient grace doesn’t work for you, then think of the role of the imago Dei (the Image of God), and how that image acts to shape and transform us.

From Aric Clark: Quakers were at the forefront of the abolition movement, have been behind a lot of prison ministry, opposition to capital punishment, and supporters of conscientious objection: what is it in Quaker theology or practice that spurs them to take such counter-cultural positions on issues of violence?

I honestly have no idea. I have no idea because it seems like those are good things for Christians to be doing—things that Jesus commanded his followers to do. So it seems like anyone who is a Christian should be doing exactly those things, and I am utterly at a loss for why Quakers are peculiar in enacting this strong Christian witness in the world.

I realize this has harsh implications, but it is my honest answer: I think Quakers take counter-cultural positions on issues of violence because they take the gospel and the teachings of Jesus seriously, and that is exactly what Jesus says to do.

From Elizabeth: What role does the Bible play in Quakerism exactly? If my understanding is correct, Quakers believe the leading of the Holy Spirit is more authoritative than the words of the Bible. If this is so, how do you reconcile the contradictions which seem to arise (for example, rejecting communion and baptism)? Does this view of Scripture make it frustrating to "debate" with other Christians, which can often lead to verse slinging? Or am I just completely misunderstanding your view of Scripture?

Practically, the Bible provides a common reference point at Durham Friends Meeting — a collection of narratives and common stories in the Meeting. There is a lot of interest in studies of the Bible across Quakerism as a whole, although people come to that study from a variety of histories of exposure.

Traditionally, the Bible has been the primary tool for Quaker apologetics and for Quaker understandings of their faith. Quakerism started with people who were well-versed in the Bible realizing that most of what the professors and churchmen taught was not biblical at all. Worse, many of those commandments laid out by Christ in clear language in the Bible were totally neglected — sometimes, even the exact opposite of the Bible’s plain mandate was being practiced! So, traditionally, Quakers were a people who placed an extreme emphasis on the scripture, to the point where scripture trumped church teaching and they got into a lot of trouble.

In following their lead, debates with other Christians often takes the form of analyzing the Bible carefully more than slinging proof-texts. An example of this can be seen in the conversation about sacraments below. Ultimately, it usually ends with even the most ardent sola scriptura Lutheran appealing to tradition, where I simply do not follow.

Another characteristic of Quakers and the Bible is that Quakers have traditionally been serious about viewing the Bible as a message of today. For Quakers who relate to the Bible this way, the world is populated with Pharisees and Romans, Pharaohs and Ahabs, Pentecosts and still small voices. This means that any moment in the Bible is a potential new moment to be—and this leads to some radical moves, like people being called to witness publicly through nakedness (c.f. Isaiah 20:2). Perhaps it seems odd to you to approach the Bible this way, but in many ways, this method of reading the Bible is actually similar to the way the black church tradition has read the Bible (especially Exodus).

With respect to the contemporary Quaker movement, the answer is a lot trickier. The theological role of the Bible is controversial in many Quaker circles, especially since Quakerism acts as a last desperate handhold for many Christians who feel abused by Biblical literalism and fundamentalism. So if you were to ask this question to any other Quaker, you will almost certainly get a profoundly different answer. But here is my answer, and I am under the impression that it is generally resonant with the conservative Quaker tradition.

Let me begin by saying that the Bible is not “The Word of God”. Jesus is “The Word of God”. Jesus is not the BIble. Ergo, “The Word of God” is not the Bible.

So what is the Bible? I believe that the Bible is a faithful record of God’s revelation. I believe its source was the Holy Spirit, and therefore I cannot believe the Holy Spirit is more authoritative than the Holy Spirit’s own message within the Bible, nor can there be contradictions between the Holy Spirit and its message.

I do, however, believe that just like the church, the received text is subject to corruption by human sin. One clear example is the fifth-century interjection of “without cause” into Matthew 5:22, changing from “never be angry” to “never be angry without cause” (as though people who are angry ever think they don’t have cause). Yet despite that reservation, I am extremely reluctant to dismiss or ignore the words of the Bible, and I use the Bible as a way to tune my ears to the Holy Spirit, just as listening to a recording of a person’s voice can help you pick that person’s living, present voice out of a crowd.

From Kris Anne: I am drawn to the idea of a service conducted mostly in silence, with a few people standing to share a word, given to them for the faith community.... but on a very practical level, as a mom of two young children, I have to ask -- What in the world do you do with the kids, who I'm sure would disrupt the whole thing (at least mine would, to be sure)? :)

Chris Benz, who also goes to Durham Friends Meeting, explained the practicalities of our group in the comment section last week. (Each service begins with 15 minutes of silence with children in the room. Babies babble and toddlers chatter, but most of the children are amazingly quiet. After the first 15 minutes, most of the children go off for 45 minutes of "First Day School." Parents have the option of leaving their children at First Day School for the entire hour if that's what works best for them.) I would just add that adults who find the kids too squirmy or noisy can either attend an earlier meeting, or they can simply sneak in after the first 15 minutes with the parents who just walked their kids to First Day School.

I will say from experience, however, that the ministry of children — even the ministry of cooing and gurgling babies — can be a very profound experience that can really set a tone for the meeting. Also, kids in Quaker meetings seem to usually recognize the palpable sacredness of the silence, and so they seem to be able to behave better than one might expect. But I am also a Minnesotan transplant, so maybe that’s just my Lake Wobegon sensibility about kids in my community...

From Megan: I've always found the Quaker view of sacraments difficult to understand because Jesus himself participated in the sacraments. Indeed, he instituted them--at least in the case of the Eucharist. If anyone had a strong enough sense of God to not need these imperfect external observances, surely it was Jesus. Yet he still seemed to place high value on them. Can you explain your view?

Without a doubt, more blood and ink have been spilt over this issue than any other. The only point on the sacraments shared among all Quakers is that sacraments are not necessary for salvation. You will also commonly find a cynicism about the sacraments’ efficacy as part of that. So that’s the general Quaker statement.

Personally, this is an issue I wrestled with quite a bit as a Quaker student at a Methodist divinity school. Keep in mind I speak solely from my own understanding and position:

Let me start by setting aside the word “sacrament” itself, because such language isn’t Biblical. The word comes from Latin, and even though the term is often tracked back to the Greek for “mystery”, you’re still not going to find the word used in any Biblical usage which reflects the technical meaning we construct for “sacrament”. Instead, I am going to talk about “ritualized outward observance”, since that seems to be the nub of the issue.

On the issue of ritualized outward observances, you and I differ on our assumptions: I do not believe that Jesus instituted any ritualized outward observance or commanded them to his disciples. I think the best case you can make for Jesus instituting a ritualized outward observance is ritualized foot-washing based on John 13, but that’s about it. All the other ritualized outward observances that people participate in purportedly based on the Bible — especially the Eucharist — come from pretty shaky constructions which, once I considered them carefully, I did not find particularly convincing.

If you want to see what it really looks like when God wants you to do a ritual outward observance, see the description of Passover in Exodus 12, Exodus 13, Leviticus 23, and Deuteronomy 16. If God wants you to do something, God lets you know in no uncertain terms. Scripture isn’t shy about it.

On the other hand, the ritual of the Eucharist is never explicitly laid out or commanded in the Bible. It’s purportedly cryptically hidden beneath the words of John 6, and it’s modeled after the Last Supper, although that isn’t clearly a model for a repeated ritual, either. Compared to the instructions for Passover, Scripture seems awfully cagey on this point which—according to the church hierarchy—is vital for salvation.

Now, Jesus did submit to the sacrament of water baptism (what Quakers call “John’s baptism”), but is never recorded as baptizing with water. In fact, in John 4:1-2, Jesus is explicitly identified as not baptizing. Instead, Jesus is offering the Living Water to the Samaritan woman in a story that explicitly identifies how Jesus’ baptism differs from John’s. This idea is repeated throughout the gospels, such as in Luke 3:16 and its synoptic parallels, as well as John 1:26-33. The most emphatic distinction is in Acts 1, especially when one includes the emphasizing word that exists in the Greek but is oft-neglected in translation— “John baptized completely with water, but in a few days you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit.” This is echoed via Peter’s memory in Acts 11:16. So baptism is spiritual, not a rite of water.

If you want to see me engage in a more careful apologetic on spiritual baptism, check out this paper I wroteon spiritual baptism and the boundary of the church. If you want the most thorough, thoughtful, and influential treatment of this in Quaker history, see Robert Barclay’s Apology for the True Christian Divinity, especially the Twelfth and Thirteenth propositions. Encountering and checking the arguments in that text shifted me from attending Durham Friends Meeting as a stop-gap to identifying as a Quaker.

From Megan: Also, I've always felt as though Quakers are reacting against a view that many thoughtful Christians do not hold. Yes, all of life is holy. I don't necessarily see that as a reason to dispense with the sacraments. Many Christians I know (and I am one of them) would say that the very physical natural of the rituals reminds us that we have an embodied, enacted faith--and that embodiedness and enactedness is (if those are words) is just want enables us to see all of life is sacred. Am I way off base in my understanding of your view?

The argument Megan references is that Quakers don’t need sacraments because we recognize all of life is a sacrament. I must admit that is something I have heard Quakers assert, although it seems to mainly come from more liberal and less conservative Friends. It is not my position, so I won’t attempt to defend it.

What I will note is that despite the lack of ritualized outward observations, on the whole Quakers don’t seem to have a problem remembering that we have an embodied, enacted faith, nor a problem recognizing that all life is sacred—hence the question above about our notable counter-cultural activities. So the argument that Christians require sacraments because otherwise we get all up in our head and detached from the world is just empirically false.

In my own case, I have never had the experience of the physical nature of the rituals reminding me of my embodied, enacted faith. When I experience the sacredness of life, that experience seems to stem from encountering its organic, eternal, and interconnected nature, not from fixed flat rituals in stone cathedrals.

To sum up: as far as I’m concerned, if physical rituals work for you and deepen your faith, then by all means have them — whatever it takes to get you to experience God and commune with your Inner Light is wonderful for you. My problem comes in when people start saying the rituals are somehow mandatory for life in Christ, which seems to be biblically, theologically, and empirically unsupported. So as the Body of Christ, let’s stop fighting each other and breaking ourselves apart over our differing aesthetics.

From EZK: How would a Quaker explain the gospel to a nonbeliever?

By doing something like this. Or by living a life of integrity—not just integrity in word and deed, but integrity among disparate values and their resulting actions. Most of all, by speaking and living plainly and honestly, aspiring to respect the infinite value of all people.

But you probably mean “what words would a Quaker use to explain the gospel?” I have to admit that’s a hard question to answer. Quakerism isn’t a system—an orthodoxy; Quakerism is a system of practices—an orthopraxy. So it is not at all clear what “a nonbeliever” means to a Quaker.

If you want to talk about someone who does not believe that Jesus is Lord and Savior, the first step is to show them that the advice Jesus gives about how to live is, in fact, the recipe for personal and world peace. I’d probably sound a lot like Leo Tolstoy (although he wasn’t a Quaker), so you could read "What I Believe" to get a sense of the line of thought. But speaking about this would have to be a very personal effort.

Thank you so much for the opportunity to share my faith with you. I will monitor the comment field and try to answer some questions, and if I can’t find the answers, I’ll pass the comment along to someone who does. And certainly go visit your local Quaker meeting house and ask questions around there: Durham Friends Meeting has “Quakerism Q&A” after meeting on the first Sunday of each month, and I bet other meetings are similarly welcoming of your questions.

© 2011 All rights reserved.

Copying and republishing this article on other Web sites without written permission is prohibited.