Hell Series: Ask a traditionalist 1 (free will, postmortem repentance)….response

by Rachel Held Evans

We’re taking advantage of our “Ask a…” series to talk with some of today’s leading theologians about the difficult topic of hell. Earlier this month, Edward Fudge responded to your questions about conditionalism (sometimes called annihilationism)—the view that immortality is conditional upon belief in Jesus Christ, so the unsaved will ultimately be destroyed and cease to exist rather than suffer eternally in hell. Later, Robin Parry responded via video to your questions about Christian universalism—the view that one day God will reconcile all people to himself through Jesus Christ.

As I began exploring options for the view typically referred to as “traditionalism”— that hell is a place of eternal torment—I realized there are a variety of perspectives to consider. For example, a Calvinist will likely view hell much differently than an Arminian….as would someone who identifies as an inclusivist as opposed to an exclusivist. Some, like today’s guest, believe in postmortem repentance, while others do not. So our interview today will not be the last entry in our hell-themed series! I’d like to also include a Calvinist, and perhaps a rabbi, as several of you suggested.

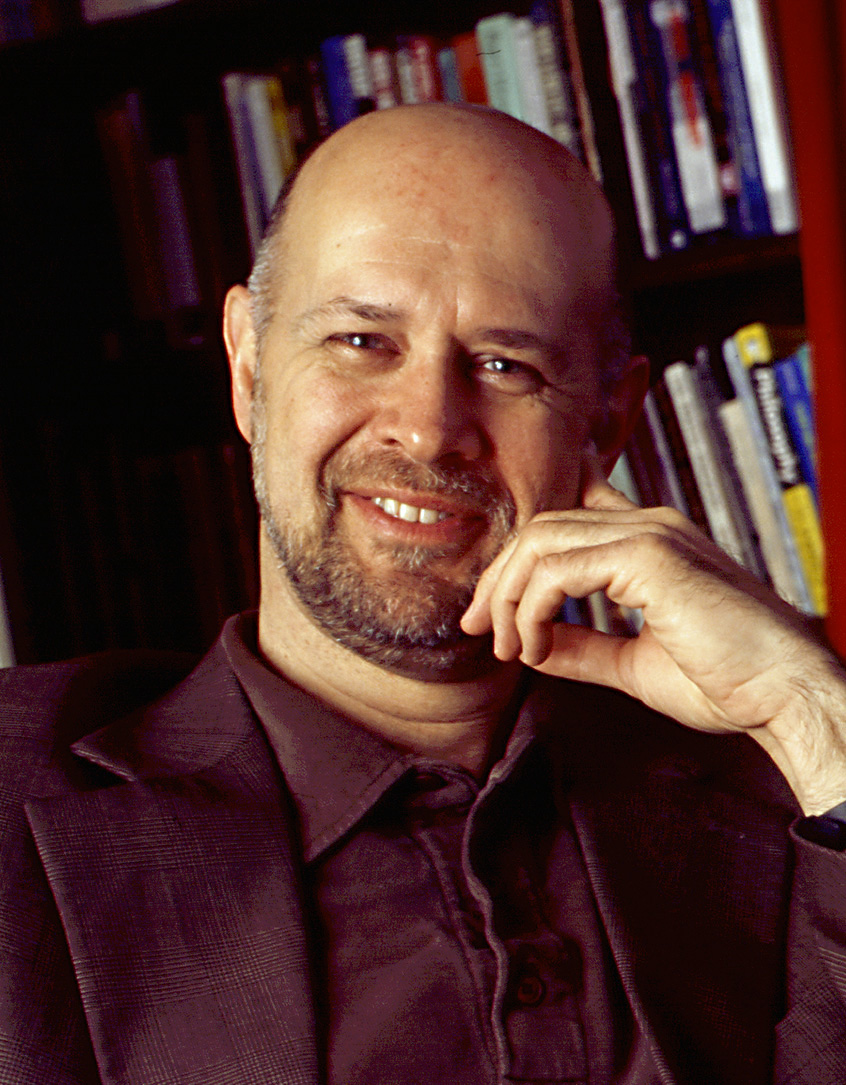

That said, today’s guest is a perfect fit for the series, and I think you will be delighted with how thoughtfully and thoroughly he responded to your questions. Jerry L. Walls was born and raised in Knockemstiff, Ohio. He has a PhD in philosophy from Notre Dame, and is the author of over eighty articles and reviews, and a dozen books, including Why I am not a Calvinst (with Joseph Dongell, IVP, 2004) and a trilogy on the afterlife: Hell: The Logic of Damnation (Notre Dame, 1992); Heaven: The Logic of Eternal Joy (Oxford, 2002); and Purgatory: The Logic of Total Transformation (Oxford, 2012). He is also the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology (Oxford, 2004). His co-authored book (with David Baggett) Good God: The Theistic Foundations of Morality (Oxford, 2011) was named the outstanding book in apologetics and evangelism by Christianity Today in their annual book awards. He has appeared on numerous radio shows including NPR’s “Talk of the Nation” and was interviewed for the documentary “Hellbound?” Before coming to Houston Baptist in 2011, where he is Scholar in Residence, he was a Research Fellow for two years in the Center for Philosophy of Religion at Notre Dame.

Jerry holds a traditional view of hell in the sense that he believes hell is a place of conscious, eternal misery. But he says he agrees with C.S. Lewis’ famous line that "the doors of hell are locked on the inside." His view is a modification of the traditional view in the sense that he believes God always welcomes sincere repentance, even after death. Unfortunately, he says, some will never exercise that option.

You asked. Jerry answered.

Enjoy!

###

From David: Given the possibility for postmortem salvation, your view, in principle at least, doesn't preclude universal reconciliation, does it? Would it be fair to call yourself a "hopeful universalist"? Or is the logic of your position at least compatible with (hopeful) universalism?

Indeed, in principle my view does not preclude universal salvation. In fact, that is exactly what I believe God desires (I Tim 2:4; 2 Peter 3:9). He is the God who does not rest content with having 99 sheep in the fold, but continues to seek the one who is lost, and rejoices when he is saved (Luke 15:3-7). So in view of this, eternal hell is an entirely contingent reality. There is nothing necessary about it. God does not need to damn some people forever in order fully to glorify himself, in order fully to be God, as some Calvinists would have it. To the contrary, God would prefer it if hell were empty.

Eternal hell only exists on the condition that some of God’s free creatures reject God’s love and grace and persist in doing so. So the reason I believe in eternal hell is because I believe some, unfortunately, will in fact persist in refusing grace, and be lost forever, and that this sad truth has been revealed to us.

I find myself in the ironic situation that I would be delighted if one of the things I have been defending throughout my career turns out to be wrong. It is at least conceivable, and perhaps possible as well, that the traditional interpretation of those texts that have been taken to teach that that some will in fact be lost is a mistaken interpretation. I hope it is, and that my universalist friends like Marilyn Adams, Robin Parry and Tom Talbott turn out to be right. I am not convinced by their interpretations although I do think they are at least plausible. But I want to be first in line to celebrate if I am wrong.

(For a defense of postmortem grace, see Purgatory: The Logic of Total Transformation, chapter 5; see also Kyle Blanchette and Jerry L. Walls, “God and Hell Reconciled,” in God and Evil, ed Paul Copan, et al.)

From Matt: Revelation 14:9-11 portrays the eternal torment of the condemned as taking place "in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb" (14:10). What does this mean? And how should we understand this portrayal in relation to other traditional images of hell as banishment from the presence of Christ?

Well, I’d start here with Paul’s sermon at Mars Hill, where he observes that God is “not far from each one of us. For in him we live, and move and have our being” (Acts 17:27-28). In this passage, Paul is applying this point to people who may be seeking God, but have not yet found him. So the point here is that even people who may be “far” from God in terms of meaningful, loving relationship are still “close” to him in the sense that he continually sustains them in existence.

So the unhappy creatures in this text in Revelation are in the presence of the Lamb by virtue of the fact that he sustains them in existence, and they may even be aware of this fact. However, they are utterly separated from him by their sinful rebellion.

Indeed, the paradoxical nature of this observation may illumine why fire is used as an image of the torments of hell. Fire in the Bible is a common image for the presence of God, not his absence (cf Deut. 4:24; 5:24-5; Psalm 50:3; Hebrews 12:29). But his presence is experienced very differently by those who are rightly related to him, as opposed to those who are not.

David Hart has noted that there is a long theological tradition, particularly in Eastern Orthodoxy, that “makes no distinction, essentially, between the fire of hell and the light of God’s glory, and that interprets damnation as the soul’s resistance to the beauty of God’s glory, its refusal to open itself before the divine love, which causes divine love to seem an exterior chastisement” (The Beauty of the Infinite, 399).

As the Psalmist noted, there is no place where we can successfully flee from God’s presence (Psalm 139:7ff). The God of love is everywhere, and we cannot exist a millisecond without his sustaining grace and power. But our freedom does allow us to refuse his love and go our own way, even as it remains true that “in him we live and move and have our being.” If that is our choice, his glorious love will be experienced like a burning fire rather than “the spring of the water of life” that will deeply quench our thirst (Revelation 21:6).

Can you explain what you mean when you talk about "optimal grace"? And how does the doctrine of election, as understood by some Calvinists, provide an unsatisfactory or incomplete view of God’s grace as it relates to hell?

This idea is central to my view of hell, and also to purgatory, so I will try to make this clear in a reasonably concise way.

Let me begin my explanation by saying what is involved in choosing hell. People do not choose to go to hell as a direct choice. It’s not like anyone says, “hey, I really want to go to hell”! Rather, they choose to go to hell by resisting grace and choosing evil. And not just choosing evil initially or partially. After all, we all choose evil initially by virtue of being fallen. What defines the choice of hell is that God and his love are decisively rejected and evil is decisively chosen instead.

Here is where optimal grace comes in. In short, optimal grace is whatever form and measure of grace is best suited to elicit a positive response from us, without overriding our freedom. Because we are all different, the exact nature of this will vary from person to person. But the important idea is that if God truly loves each one of us, and truly desires our salvation, he will offer his love and grace to each of us in the way that is optimal to elicit a positive response.

Pretty clearly, not everyone has such grace in this life, and that is one of the reasons I believe in postmortem grace and repentance. What this means is that in the long run, everyone has an equal opportunity to be saved. In the afterlife, God can find ways in his infinitely creative wisdom to give everyone the best opportunity to respond to the gospel.

What this underscores is that no one goes to hell because of ignorance or lack of opportunity to be saved. Nor does anyone go to hell for rejecting a distorted or garbled view of Jesus and his amazing love. No, emphatically not! You go to hell for rejecting Jesus, not a caricature of Jesus. You go to hell for spurning the amazing grace he showed us in the cross and resurrection, not for being ignorant of it.

But in order for that to happen, you have to be properly and truly aware of who he is and the truth and beauty of his love. Only when you are properly informed of the truth can you freely, deliberately and decisively reject it. In other words: a decisive choice of evil is only possible given optimal grace.

So that is what is amazing and even perplexing about the idea of hell. A lot of people assume that if optimal grace were true, universal salvation would automatically follow. But again, I would insist that eternal hell is not in any way due to some having less opportunity to be saved than others. I believe some people will decisively reject God’s love and be lost, even though he gave them every opportunity to repent and be saved.

And thanks for raising the Calvinist connection because this is something I am always happy to talk about. Actually, however, the problem with the Calvinist view of election is much worse than being merely unsatisfactory or incomplete. As Calvinists see it, some people get irresistible grace by which they will inevitably be saved, and others are completely passed over with respect to saving grace, and are inevitably damned. The unequal distribution of grace here is poses insurmountable problems for God’s goodness.

Indeed, Calvinism and eternal hell are a lethal combination that is biblically, logically and morally indefensible. It can only be defended by forthrightly admitting that God does not love everyone (which Calvinists are often loath to do, for good reason), or by engaging in misleading rhetoric, which is the far more common strategy. If you want to be a Calvinist, you should be a universalist. I do not have the space to defend those claims here, but I have done so elsewhere. See my You Tube videos entitled “What’s Wrong with Calvinism” as well as my co-authored book, Why I am not a Calvinist.

Now what I find interesting, however, is that many people who are not Calvinists believe that God gives everybody at least some chance to be saved, but not optimal grace. They hold that at least some ray of light has come into every life, or that everyone has heard the gospel at least one time. They affirm that everyone is given at least what we might call “minimal grace.”

And why do they insist on this? Because they want to be able to say that God is fully just in damning such people. In other words, it is important that everyone have enough grace or opportunity for salvation that God can be just in sending to hell those who die without faith. But optimal grace is not required for this.

Now here is the question: If God can make sure everybody has at least some real opportunity to be saved, why could he not make sure that everyone has optimal grace? Does he lack the creativity, the wisdom, or the means to do this? And more importantly, if he could do this, is it not the case that he would do so? Why would he not?

So here is one of the most fundamental issues in how we conceive of God, one that will profoundly shape not only our view of hell, but our entire theology. Does God genuinely, deeply, love all persons and desire to save them? Or is his only concern to give them enough revelation and grace that he can justly damn them if they die without faith?

There is far more to say, of course, but this answer is already rather long. If you want to explore this further see Hell: The Logic of Damnation, chapter 4; Purgatory: The Logic of Total Transformation, chapter 5, and the essay “God and Hell Reconciled, cited above. If you want just a bit more on the last point, see this video.

From Tanya: I'm having a hard time wrapping my head around this position. While it makes beautiful, logical sense --(you get to keep Hell, and a merciful picture of God to boot) what would this look like? Who in their right mind would sit in hell, "in conscious, eternal misery" and simply refuse to repent? At that point, believing in the existence of God doesn't seem tough, I mean, somebody is responsible for the hell you are in -- so who would sit and stew for eternity "on principle?" Can you paint me a believable picture of a specimen of humanity who might do this?

Let me begin here by saying I am with you in thinking there is something absurd in the idea of someone freely choosing eternal hell. I wrote a defense of eternal damnation for my PhD dissertation at Notre Dame several years ago, and my biggest challenge was trying to make sense of how anyone could freely choose the misery of hell. I am currently writing a popular level book tentatively entitled Heaven, Hell and Purgatory: Life as Comedy, Life as Tragedy, Life as Story. I just finished the chapter on hell, and I am still struck by how crazy this can seem. And yet, the decisive choice of evil does have a certain logic and we can make at least some sense of it.

What is clear is that people who do this are not altogether “in their right minds.” That is, they are not thinking clearly, they are not embracing the truth about themselves and about God. They are deceived at a deep level. And yet, they are not deceived in the sense that they are innocent victims. Rather, they are self-deceived.

If you want a believable picture of this, read CS Lewis’s book, The Great Divorce. In case you have never read it, the premise of the book is that a group of people (“ghosts”) from hell take a bus ride to heaven and are invited, indeed, implored to stay. Common sense, of course, assumes that they would jump at the chance. But what Lewis depicts, with remarkable psychological and emotional plausibility, is how almost all of them spurn the offer and return to hell.

As Lewis famously remarked in another book, “the doors of hell are locked on the inside.” It is not that God locks them in against their will, but they are not willing to come out. Lewis went on to comment: “I do not mean that the ghosts may not wish to come out of hell, in the vague fashion wherein an envious man ‘wishes’ to be happy: but they certainly do not will even the first preliminary stages of that self-abandonment through which alone the soul can reach any good.”

One of the more memorable of the characters that illustrate this truth is a “Big Ghost” who takes the trip to heaven bent on getting his “rights.” When he gets there, he is greeted by a man who was one of his employees in this life. He is outraged at this because the employee had murdered someone, and he cannot fathom how the employee can be in heaven, while he has been in hell. What he simply cannot (will not) understand is that he too, needs grace, that he too needs to be forgiven for his own sins and transformed before he is fit for heaven. When he realizes this, and that his former employee is the very person sent to instruct him, he decides to return to hell.

“So that’s the trick, is it?” shouted the Ghost, outwardly bitter, and yet I thought there was a kind of triumph in its voice. It had been entreated: it could make a refusal: and this seemed to it a kind of advantage. “I thought there’d be some damned nonsense. It’s all a clique, all a bloody clique. Tell them I’m not coming, see? I’d rather be damned than go along with you….” It was almost happy now that it could, in a sense, threaten.

Notice particularly that the Ghost is “almost happy.” What this points out is that hell has its pleasures, and its own version of “happiness.”

I’m sure all of us can relate to the pleasures of resentment, bitterness, self-righteousness and so on. It is not hard to see that anyone who is resentful is not truly happy, indeed, they are miserable. But those who choose to hold on to their resentment do enjoy a perverse sort of pleasure and a distorted sense of satisfaction. To anyone who urges them to repent and give it up, they may well give the bird and insist they are doing just fine, thank you.

I have tried to make philosophical sense out of this in chapter 5 of Hell: The Logic of Damnation, as well as in the popular book I am currently writing. Also, keep your eyes open for Kevin Timpe’s forthcoming book Free Will in Philosophical Theology, which has a very insightful discussion of the logic of choosing evil, including damnation. But again, I’d start with Lewis.

Similarly, Nate asked: First, what is the nature of the "conscious, eternal misery?" Is it physical (fire, pain, etc.), is it emotional/spiritual (loss, separation, despair, etc.), or is it both? Second, if there is opportunity for repentance upon experiencing conscious misery, why would some not choose it? This seems to go against the human instinct for survival and comfort.

I think the essence of the misery of hell is the natural unhappiness that results from resisting the love of God and having a character decisively formed by evil, with all that that entails. For instance, such a character cannot enjoy meaningful relationships, which are essential to human happiness. The nature of such misery is not hard to understand, indeed, there is a profound continuity between such misery and the misery evil naturally produces in this life. John Wesley put it like this:

For it is not possible in the nature of things that a man should be happy who is not holy….The reason is plain: all unholy tempers are uneasy tempers. Not only malice, hatred, envy, jealousy, revenge, create a present hell in the breast; but even the softer passions, if not kept within due bounds, give a thousand times more pain than pleasure.

However, I also believe that the misery of hell includes a physical dimension for the simple reason that human beings are embodied beings by nature, and the damned will be resurrected in their bodies. I do not believe the fire is literal but rather an image, just as I think “the worm that does not die” is an image or a metaphor (Mark 9:48). As has often been pointed out, hell is also pictured as darkness (eg Matthew 22:13), and literal fire and darkness are incompatible. This does not mean that the realities imaged by fire, undying worms and darkness are not terrible because that language is metaphorical rather than literal. After all, a metaphor communicates because it the reality it depicts is similar to the image that is used.

I discuss my view of the misery of hell in detail in chapter 6 of Hell: The Logic of Damnation.

From Rachel: So the most common Bible passage cited by those who oppose the possibility of postmortem salvation is probably Hebrews 9:27-28: "And inasmuch as it is appointed for men to die once and after this comes judgment, so Christ also, having been offered once to bear the sins of many, will appear a second time for salvation without reference to sin, to those who eagerly await Him." How do you interpret these words from Priscilla and Aquilla? (Okay, so that last bit is a personal theory about the authorship of Hebrews, but the question still stands!)

Well, I think this text is way overrated by those who cite it against the possibility of postmortem conversion. Not the text itself, because it’s pretty hard to overrate Biblical texts, but rather the way the text is interpreted. In short, those who cite this text for that reason are trying to squeeze more out of it than it actually says. So what does it say? We die once. Well, I certainly agree with that, and I would guess most proponents of postmortem salvation do not posit that we die multiple deaths.

Next, it says that after we die, there is judgment. And of course I agree with this. But notice: it does not say judgment is immediately after death, nor does it say, (if there is an immediate judgment) that it is final. Indeed, most traditional theology holds that the final judgment is yet to come. So there could well be a preliminary judgment immediately after death that would judge one’s life to that point, but that judgment could still allow for repentance.

The text goes on to compare and contrast the first and second comings of Christ, but again, I see nothing there that rules out postmortem repentance.

It is also worth emphasizing that God’s word of judgment often leads to repentance and ends in mercy and redemption. For just one example, consider Jonah’s word of judgment to Nineveh: in forty days, Ninevah will be overthrown (Jonah 3:4). Of course, as the story turns out the Ninevites repented and their city was not overthrown. Did God change his mind? No, he did not. Implicit in the word of judgment was an invitation to repent. The Ninevites, however, did change their minds, which is what repentance literally means, a change of mind. Had they remained impenitent, the judgment would surely have fallen.

From Chris, and the community at rethinkinghell.com: Proponents of the eternal conscious torment view typically hold to the biblical teaching that the unsaved are likewise resurrected and that both body and soul are subject to hell. However, they believe that these resurrected bodies of the lost will live forever, albeit separated and isolated from God. Yet the Bible explicitly says that only God has immortality inherently and that immortality is brought to light through the gospel and granted to the glorified saints who persevered in the faith to the end, whereas it does not appear to say anywhere that immortality is granted to the unsaved. So when eternal conscious torment is the very question at hand, what biblical evidence would you point to as teaching that the resurrected bodies of the lost will likewise be made immortal?

Immortality, like eternal life, is far more than ongoing conscious survival, or even the resurrection of our bodies. Or to use a distinction philosophers often employ, continued survival is necessary but not sufficient for immortality. Scripture of course speaks of a resurrection of both the just and the unjust (John 5:28-9; Acts 24:15). Immortality properly speaking is the resurrection to the fullness of life in relation to God and others for which we were created. It is the glory that comes from having the character and likeness of Christ (2 Cor 3:18; 4:4-7).

It does not follow, however, that to fall short of glory, as sin inevitably causes us to do (Romans 3:23), is to lose existence altogether. The resurrection of the unjust can be a resurrection to ongoing existence even though it is not resurrection to the immortality of life with God. I believe that texts like the one from Revelation 14 cited above give us reason to believe that even those who reject God’s gift of salvation and the glorification that entails still remain in conscious, embodied existence. Indeed, they remain in relationship to God even though it is a relationship of sin and rebellion.

I will grant you the biblical data on this matter is debatable. But if hell is freely chosen, as I have argued, and is not the torture chamber sometimes depicted, the conditionalist view loses a lot of its motivation. God’s perfect love and goodness is perfectly compatible with those persons who refuse the gift of salvation and immortality, but whose ongoing existence is defined by an ongoing rejection of the very God of love in whom they continue to “live and move and have their being.”

From Preston Sprinkle: Are there degrees of punishment in Hell? And if so, could those who receive a "lesser" sentence ultimately be annihilated? For instance, a 15 year old Saudi girl has been raped her whole life, and has just met a Christian on the streets who gave her a 5 min gospel presentation (in Arabic), making her now accountable, but seconds later she gets hit by a bus: will she be kept alive by Jesus so that she will consciously feel the most tormenting pain for ten trillion years. And more? And will she sit alongside Hitler in his misery? I ask not facetiously or rhetorically (assuming a right answer), but because I've been faced with the same question ad nauseum.

Yes, I do think scripture gives us reason to think the misery of hell varies in quality as well as intensity, depending on the patterns and kinds of sin committed. A person consumed with hatred, for instance, likely experiences a different sort of misery than one who simply let his life and character be formed by following his lusts and desires. The different forms of suffering Dante depicts, as well as Lewis in The Great Divorce, is very suggestive in that regard.

As for the scenario with the 15 year old girl, well, that is the very picture of “minimal grace” and the very sort of thing that would be ruled out by my view of optimal grace. Given this story, we have no reason to think this girl has really understood the gospel, let alone well enough to reject it decisively. The assumption that she would be lost forever simply because she heard one garbled sermon makes the doctrine of hell as often defended a moral and theological absurdity.

From Eric: Whoa, whoa, whoa. This is not directly related to the post, but there's seriously a place called Knock 'em stiff, Ohio?

Not only is there really a place named Knockemstiff, Ohio, but it has also achieved notoriety fairly recently in literary circles. This is due to my friend and high school classmate (though he dropped out his Jr. year and did not graduate with our class) Donald Ray Pollock, who lived up the road from me in Knockemstiff, and has used it for the setting in his critically acclaimed fiction. Don burst on the literary scene in 2008 after working 32 years as a truck driver in a paper mill when he published an extraordinary short story collection entitled Knockemstiff. He followed that up a couple years later with a novel, The Devil all the Time, which won several awards including “Badass Book of the Month” from GQ. He is currently finishing his third book, another novel, on a Guggenheim fellowship.

Before he published his collection of short stories, I arguably had the title of “Greatest Writer from Knockemstiff.” Now I have to content myself with the thought that I am likely the most accomplished writer in my high school graduating class.

Don’s books are a bracing read, but be forewarned that they are on the far end of “raw and gritty.” In fact, it is not too much of a stretch, given our current discussion, to suggest that his books provide some vivid glimpses of hell. Here, by the way, is my review of The Devil all the Time.

###

Thanks again for your questions! You can check out every installment of our interview series—which includes “Ask an atheist,” “Ask a nun,” “Ask a pacifist,” “Ask a Calvinist,” “Ask a Muslim,” “Ask a gay Christian,” “Ask a Pentecostal” “Ask an environmentalist,” “Ask a funeral director,” "Ask a Liberation Theologian," "Ask Shane Claiborne," "Ask Jennifer Knapp," "Ask N.T. Wright and many more— here

.

© 2013 All rights reserved.

Copying and republishing this article on other Web sites without written permission is prohibited.