an excerpt from A Year of Biblical Womanhood:

"Mary, she moves behind me

She leaves her fingerprints everywhere

Everytime the snow drifts, every way the sand shifts

Even when the night lifts, she's always there.

Jesus said, Mother I couldn't stay another day longer,

Flies right by and leaves a kiss upon her face

While the angels are singin' his praises in a blaze of glory

Mary stays behind and starts cleaning up the place."

- Patty Griffin, "Mary"

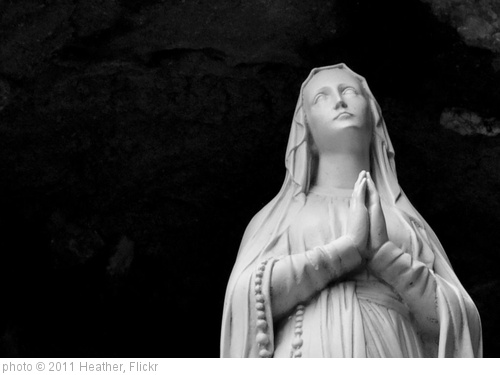

There’s a misconception among some Protestants that Catholic and Orthodox Christians worship the Virgin Mary. The icons, the rosary, the crowning, the Marian hymns—it’s all a bit much, and so they dismiss out of hand any language of veneration that might elevate the mother of Jesus to a place of special esteem and call it idolatry.

It’s a shame, really, because Mary has so much to teach us.

Like Eve, the mother of Jesus has been subjected to countless embellishments of the religious imagination— some of them fair, some of them more reflective of the prejudices and projections of the societies from which they came. Often she appears as a foil to eve: the redemption of womankind and the standard of female virtue. Standing triumphantly atop the temptation scene on Notre Dame Cathedral’s western facade is the statue of the crowned Mary, her royal robes grazing the top of the eve’s head. “What had been laid to waste in ruin by this sex,” Tertullian wrote, “was by the same sex re-established in salvation. Eve had believed the serpent; Mary believed Gabriel. That which the one destroyed by believing, the other, by believing, set straight.”

That a woman who managed to be both a virgin and a mother is often presented as God’s standard for womanhood and can be frustrating for those of us who have to work within the constraints of physical law. Indeed, visions of Mary’s virtue have been amplified though the centuries, far beyond what we find in the biblical text. The apocryphal protoevangelium of James presents Mary as sinless, a perpetual virgin who spent the first three years of her life living in the temple and being fed by angels, and who somehow managed to give birth in a first-century Palestinian barn without feeling an ounce of pain. In 1854 the Catholic Church formally embraced as dogma the Immaculate Conception—the belief that Mary was born without the stain of original sin. It’s as though, over time, Mary’s feet have gotten farther and farther off the ground.

Much could be said in contrast about the “real Mary” of the biblical narrative: the teenage girl from Nazareth who gave birth on a dirty stable floor; the terrified mom who scurried frantically through the streets of Jerusalem, looking for her lost little boy; the woman who had enough influence over Jesus to convince him to liven up a wedding with his first miracle of turning water into wine; the grieved mother who wept in the shadow of the cross. But perhaps the most revealing glimpse into Mary’s true character can be found in the Magnificat—a prayer beloved by saints and Southern Baptists alike.

According to Luke’s gospel, when Mary was betrothed to Joseph, God sent the angel Gabriel to deliver an important message. His presence and his words frightened the young girl.

“Do not be afraid, Mary,” said Gabriel. “You have found favor with God. You will conceive and give birth to a son, and you are to call him Jesus. He will be great and will be called the son of the Most high. The Lord God will give him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over Jacob’s descendants forever; his kingdom will never end.”

“How will this be,” Mary asked the angel, “since I am a virgin?”

Gabriel told Mary that the Holy Spirit would come over her: The “power of the Most high will overshadow you.”

“I am the Lord’s servant,” Mary said resolutely. “May your word to me be fulfilled”

Fully yielded to the will of God, this young, peasant girl offered a bold and subversive prayer that reveals her own hopes for this special child and the future of Israel:

My soul glorifies the Lord

and my spirit rejoices in God my savior,

for he has been mindful of the humble state of his servant.

From now on all generations will call me blessed,

for the Mighty one has done great things for me— holy is his name.

His mercy extends to those who fear him,

from generation to generation.

He has performed mighty deeds with his arm;

He has scattered those who are proud in their inmost thoughts.

He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble.

He has filled the hungry with good things

but has sent the rich away empty.

He has helped his servant Israel,

remembering to be merciful to Abraham and his descendants forever,

just as He promised our ancestors. (vv. 46–55)

With this prayer, we encounter Mary as Theotokos—the Mother of God, a Greek term that sends many Protestants running for their commentaries, but which beautifully connects the humanity of Mary with her divine call. It comes from the Orthodox Church, and more accurately means “God-bearer” or, “the one who gives birth to God.” Theotokos refers not to Mary as the mother of God from all eternity, but as the mother of God incarnate. She is what made Jesus both fully God and fully man, her womb the place where heaven and earth meld into one.

At the heart of Mary’s worthiness is her obedience, not to a man, not to a culture, not even to a cause or a religion, but to the creative work of a God who lifts up the humble and fills the hungry with good things.

Madeleine L’Engle connects this type of obedience to our own everyday acts of creation. “Obedience is an unpopular word nowadays,” she wrote, “but the artist must be obedient to the work, whether it be a symphony, a painting, or a story for a small child. I believe that each work of art, whether it is a work of great genius, or something very small, comes to the artist and says, ‘Here I am. Enflesh me. Give birth to me.’ And the artist can either say, ‘My soul doth magnify the Lord,’ and willingly become the bearer of the work, or refuses; but the obedient response is not necessarily a conscious one, and not everyone has the humble, courageous obedience of Mary.”

The same applies to faith. One need not be a saint, or a mother, to become a bearer of God. One needs only to obey. The divine resides in all of us, but it is our choice to magnify it or diminish it, to ignore it or to surrender to its lead.

“Mary did not always understand,” wrote L’Engle, “but one does not have to understand to be obedient. Instead of understanding—that intellectual understanding which we are so fond of—there is a feeling of rightness, of knowing, knowing things which you are not yet able to understand.”

Like a good protestant should, I think Mary’s act of radical obedience means more when she is one of us. Imperfect. Afraid. Capable of feeling all the pain and doubt and fear that come with delivering God into the world. But I suspect I may also be a bit of a Catholic, for on the rare occasion that I yield myself fully to the will of God, when I write or speak or do the dishes to magnify the Lord, I start to see Mary everywhere.

**

Read more in A Year of Biblical Womanhood.

© 2012 All rights reserved.

Copying and republishing this article on other Web sites without written permission is prohibited.