I get a knot in my stomach every time someone asks me if I think homosexuality is a sin.

It’s a loaded, closed-ended question that requires making a sweeping pronouncement on a group of people that is far too diverse and varied to earn a single label. It’s a question that instantly lowers the level of discourse by casting the complicated continuum of human sexuality into sharp, black-and-white terms. And it’s a question I’m desperately afraid to answer for fear of losing credibility, for fear of losing friends, and for fear of being wrong.

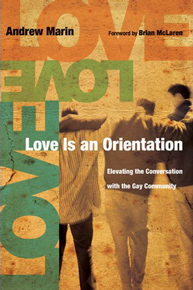

What I love about Andrew Marin’s excellent book Love is an Orientation is that it does the exact opposite.

It elevates the discourse by gently coaxing the reader into those uncomfortable gray areas where the best, most productive conversations always occur. Instead of black-and-white, Marin sees a world of color, and the deep, longtime relationships this former self-proclaimed “Bible-thumping-homophobe” has built with gays and lesbians over the years is a testimony to the fact that a more productive conservation between evangelicals and the GLBT community is indeed possible.

I finished Love is an Orientation feeling more confident—not because Marin had resolved every question in my mind and not because I agreed with everything he said or implied—but because I felt freed from the confines of those old, closed-ended questions that never seemed to get us anywhere.

There’s a lot I could cover in this review. Some things I’d love to talk about, but can’t in the interest of space include:

- Common misconceptions/ generalizations that conservative evangelicals apply to the GLBT community. (For example, I often hear from Christians that “most gay people were sexually abused,” but Marin explains that research suggests only 7 to 15 percent of the GLBT community was sexually abused in their youth.)

- Biblical/theological considerations put forth by gay-affirming churches and biblical/theological considerations put forth by more traditional, conservative churches. (Marin explores both, briefly but fairly.)

- Why the fight over gay marriage misses the point. (Writes Marin, “Let the politically active have what the politically active think belongs to them. Christians should think in God’s kingdom-encapsulated terms, not in human terms…The political world means too much to Christianity, and people mean too little.”)

What I’d like to focus on instead is the main point of the book.

Marin explains that “at a baseline level, all the GLBT community wants from God is a) to have the same intimate relationship with God that evangelicals claim to have; and b) to safely enter into a journey toward an inner reconciliation of who they are sexually, spiritually, and socially.”

Our goal as Christ-followers is not to try to cram people into whatever our behavioral ideals might be, but to lovingly help people reconnect with God. This is true in all relationships, but we must be especially deliberate in building bridges with the GLBT community as it has been so ostracized and misunderstood by the conservative religious community.

If we simply focus on loving gays and lesbians with the goal of helping them nurture healthy relationships with God, we can relax a little and trust God to lead each individual down whatever path is right for him or her.

As Billy Graham once said, “It is the Holy Spirit’s job to convict, God’s job to judge, and my job to love.”

Marin explains that we often get caught up in sexual “ideals” that result in polarized conversations and unrealistic expectations. From a straight perspective, the “ideal” is to get married and have a family. From a gay perspective, the “ideal” to come out and live a happy, reconciled life as an active gay man or lesbian woman. For many gay Christians, the “ideal” is to be celibate. Notes Marin, “What each ideal has in common is that they all focus on sex—or lack thereof—as the standard by which to judge a life.”

He continues:

There’s a fourth ideal that gets overlooked, an ideal that is not based on sex: It’s okay to be yourself before God and not conform to any of the other three ways that seem ideal to the outside world…The fourth ideal communicates God’s acceptance, validation, affirmation, and unconditional love in meeting people as they are, where they are. Some critics might think this fourth ideal is the same as a blanket acceptance of the gay identity. Others might think this fourth ideal is the same as celibacy, just renamed to try to make it more accessible. But the fourth ideal is rooted in neither. It’s an ideal focused on an identity in Christ rather than behavior—straight, gay, or celibate—as the judge of one’s acceptability.

With this in mind, Marin proposes that we leave our closed-ended questions behind for more open-ended conversations that focus on understanding one another’s stories and drawing one another closer to God.

In one of the most compelling parts of the book he notes that throughout the Gospels Jesus was asked closed-ended questions twenty-five times by both his friends and his enemies. “Yet only once during his three-year public ministry, prior to his arrest and trial, did Jesus answer a closed-ended question with a closed-ended answer (Mt 21:16).”

This was a really convicting point for me, because I often wonder how Jesus would have responded if he had been asked the question, “Is homosexuality a sin?” In fact, sometimes I feel a little irked that he didn’t address it directly!

But as I finished Love is an Orientation I felt for the first time like I had a good guess of how Jesus might respond were I to ask him that question today. I imagine him turning to me and saying, “Rachel, have I not already given you all you need to respond to your gay and lesbian friends in love? Do you really need to know how to judge other people before you can love them? Will an answer to this question make you more like me or will it just satisfy your curiosity? If you want to talk about sin, we can talk about yours. In the meantime, go and love your neighbor unconditionally. Let me, the Father, and the Holy Spirit do the convicting and the judging.”

***

Some questions:

For all—How might your conversations with (and about) the GLBT community change if the only person you were allowed to judge was yourself? How can we build bridges between the evangelical community and the GLBT community?

For my gay and lesbian readers—What’s it like to be you? Can you describe a negative conversation you have had with a religious person? What about a positive conversation?

© 2010 All rights reserved.

Copying and republishing this article on other Web sites without written permission is prohibited.